RED Matte Box Rail Mount

NOTE: Want to purchase one?

See our shop for a RED Matte Box Rail Mount

You may remember the Matte Box Flags that I laser cut a while back, or the more recent LCD Arm that I 3D printed, well, there’s another accessory done now, and it took months and months to get it done. (Well, most of those months were due to procrastin—I mean, working on other projects.)

So our story begins with the RED Matte Box, which fits fine on the RED Lens, but when you slap a Zeiss Super Speed in place, the Matte Box can’t attach to it, no worries, RED sells two parts to solve your problem.

Just drop $350 USD on two parts and you can now secure your matte box to the 19mm rods. This is an ideal solution, but as you know, I’m cheap, and I’m DIY, so away we go!

Here’s how it looks underneath. Those two piece attach together and let the matte box ride the rails, and there’s some latitude for adjusting the height of things. It’s nice hardware, for sure.

Once again I commend RED on publishing nice photos of their products…

…because it’s fairly easy to clean these up and trace them and create 2D profiles that can be extruded to 2.5D designs.

That’s much better! In fact, since it’s 2D I actually laser cut some wood to do a test fitting, since my 3D Printer was down for a bit when I was working on this.

(It was a nice diversion, and honestly I just really like laser cutting things.)

Somewhere along the way though, I pretty much abandoned the idea of recreating the stuff RED has and figured I should just design my own. Maybe after the whole RED Arm debacle I realized their designs are sometimes lacking…

Anyway, I was overly complicating things, so I decided to go simple. Also, we’re 3D Printing here!

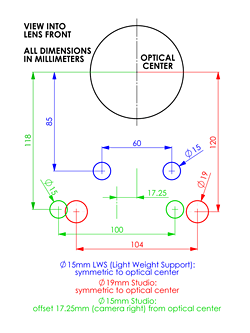

Also, if making any rod-related things, I highly recommend you grab the Rod Standard Graph PDF from the OConor site.

This is what I eventually came up with. It’s mostly an extruded shape, but it does have some holes for the bolts including bits to lock in the hex heads, just like the Arm does. I wish I could say I just 3D printed this and that was it, but it’s far from it.

While I was working on this I was also working on calibrating the RepRap after the recent repairs, so I had a bunch of issues with things not printing as well as they should, or not exactly the right size, you know, like a 19mm hole printing at 18.673mm or 21.298mm. So I moved back to a bit of prototyping.

I used the old STL to DXF trick (thought slightly modified) to create a 2D design from the original 3D file. Once I had a DXF file I could use the Silhouette Cameo to easily cut some thick paper to get an idea of size and dimensions. Eventually I was happy with how things were looking so I moved on to plastic.

Here’s the DXF file extruded to 5mm tall, with the idea being that I could print this much more quickly (and with less plastic!) that doing the full print which is 25mm tall. This worked well, and I was able to test fit it on the rods, but I was still having a few weird issues with the 19mm hole sizing.

I ended up pulling my 5mm STL file into OpenSCAD and doing a difference to subtract most of it and just leave a portion so I could print this and test the hole sizing even faster. This too worked quite well.

This all might seem like a crapload of work to get what I wanted, but there was much exploring and learning along the way, and believe it or not, that’s most of the fun in doing it for me. If I just downloaded and printed something, well, that’s good if you want a thing, but not as good if you want to learn the process of creating a thing.

The final piece, with two 1/4″ hex bolts, some nut knobs (as seen previously), and two smaller screws and wing nuts to hold the matte box in place. There was a little bit of delamination in this print. I may try it on the LulzBot TAZ 3 that we just got in at Milwaukee Makerspace, as I think it will be a good test.

Hey, it works! It fits on the rods and holds the matte box in place. Simple enough, right?

And then there was a wiki…

I’ve long been a proponent of wikis as knowledge bases within organizations. Since I discovered WikiWikiWeb in 2000, I was struck by the power and simplicity of wikis. (This was a year before the launch of Wikipedia, and many years before most people had even heard of Wikipedia!)

The first wiki I launched for a company started small, and eventually grew into a tool the Interactive department used for crucial information used by the staff. Some people believe that keeping data locked up within their own notes—or worse, just inside their own brains—creates job security. If no one else knows how something works, you become invaluable. My argument goes the opposite way, that creating a wiki and sharing all the knowledge shows your commitment to the health and well being of an organization.

During a job interview in 2006 I mentioned how I left behind a 200+ page wiki at my previous position, and without a doubt, that was the one thing that brought up the most questions from my interviewer. (The position wasn’t right for me, but I always secretly hoped they launched an internal wiki.)

Inc Magazine has a nice article titled A Micromanager’s Guide to Trust, with this great bit:

At Staff.com, Martin came up with a novel solution: He created a wiki that describes how to handle some 500 operational issues.

Exactly!

While I’m sometimes a bit too busy to do all the wiki maintenance I’d like to do, the Milwaukee Makerspace wiki has grown to become the operational manual for the organization. This is even more important when you realize that each year a new group of leaders is elected to the Board of Directors. And since the group is a “club” and not an “employer” people are free to leave when they want. (Meaning, there’s no firing or laying people off, but we do have to deal with people who just “disappear” sometimes.)

To me, this all goes back to the original idea of why I find/found the Internet so interesting. It’s about sharing information, openly and freely, with others. It’s about storing knowledge and having it easily retrievable. Wikis accomplish these things, and for that, I am mighty grateful.

(Oh, and my favorite wiki for the past fear years has been DokuWiki. Check if out if you need to implement a wiki for your organization.)

stlviewer canvas adjustment

I use Gary Hodgson’s stlviewer quite a bit, as it allows for a quick view of an STL file in your browser, and since I’ve always got a browser running, it’s often easier than launching yet anther app just to view a 3D model.

But one of the things that’s always bugged me about it was the fact that the build plate appeared to be 100mm x 100mm, which would be fine in 2010 if using a MakerBot Cupcake, but my RepRap has a 200mm x 200mm build surface…

This is much better! My models over 100mm long/wide actually fit on the build plate instead of spilling over into space. Obviously if you’re using Gary’s online version you can’t really make changes, but I just run it locally from my hard drive, so I can easily hack at it.

Just go into the js folder and in there is the thingiview folder, and open thingiview.js in your favorite text editor. Line 711 should look like this.

plane = new THREE.Mesh(new Plane(100, 100, 10, 10),

new THREE.MeshBasicMaterial({color:0xafafaf,wireframe:true}));

(Note: It’s all one line, but it’s wrapped here for readability.)

For the part that says new Plane(100, 100, 10, 10) just change it to new Plane(200, 200, 10, 10) and you’ll get a 200mm x 200mm canvas with which you can display your lovely STL file on.

(Obviously if you’re using MegaMax you should go a bit larger, perhaps 300mm x 300mm would be appropriate.)

The Toolbox that Makes Things

This is the future… a 3D Printer where you work; improving things, repairing things, and creating new possibilities. It’s here today for some people.

Here’s a nice post about Brookhaven Memorial Hospital saving money and solving problems thanks to one of their employees and a MakerBot 3D Printer. Think back to the days when the first Macs came out, and people who owned them would bring them into the office to get work done. I’ve brought my RepRap into work, but more often I just do the needed measuring and modeling and then print things at home and bring them in. (Like a recorder mount, LCD arm, or even something as mundane as a coat hook.)

Once you’ve got a “toolbox that makes things”, it’s not hard to look around and see things that could use improvement, or problems that need solving. (Recently my wife asked me to fix a loose shelf, and I was actually a bit disappointed that all it took were two zip ties to fix it. I was all ready to model and print something!)