If you’ve been following along as I develop a Learn to Solder Kit (see Part I and Part II) you’ll know that after etching the boards, we’ll need to add holes for all of the through-hole components that will be soldered into place.

I’ve been using a Dremel Drill Press we have in the Physical Computing Lab at UWM to drill all the holes. The bits are tiny, at 1mm or less in diameter. I’ve broken two already, so I’ve got a bunch more on order to replace the broken ones. The first one I broke right when I started drilling boards, probably because I was trying to drill a bit too fast. It’s important to remember that the bit needs to do the work of cutting. The tiny tools don’t work quite like the big tools you can be rough with. The second bit I broke was due to moving too fast, basically I’d drilled a ton of boards and was getting near the end and just didn’t take my time when moving the board, and slid it a bit before I fully lifted the bit out of it. Oh well…

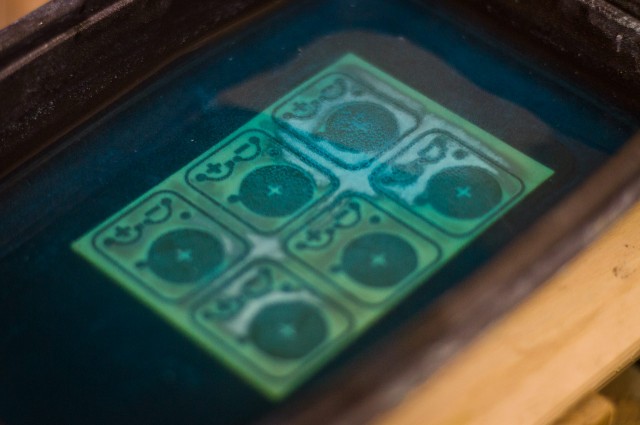

Here’s a collection of drilled boards. Some are cut apart, and some are not yet cut apart. (We’ll cover the “cutting” part in a future installment.)

You’ll notice there’s one hole that is much larger than the rest. That hole is for a wire to feed through, and I drill that hole with my big drill press. The large copper pad you see is just used as a guide, and gets obliterated by the drill.

Drilling the large holes is a quick and easy operation compared to the smaller holes for the components. You’ll notice that this drilling leaves a bit of “crap” around the hole after the drill bit is lifted out of the material, so we’re going to clean that up…

Using a much larger bit (and our hands instead of the drill press) we just lightly twist the bit around a few times in a clockwise direction. This is enough to let the bit shave away the excess material. It helps to have sharp drill bits when doing this. This too is a quick operation, with just a few twists for each hole, on the front as well as the back. Clean holes are good holes!

Here’s the difference between a cleaned up hole (left side) and a bunch of non-cleaned up holes. It is an extra step to clean things up, but when you make things (and you care) it’s just something worth taking the time to do…

Now, as I’ve mentioned, I’ve been using the Dremel Drill Press at UWM for the component holes, and while it works fine, the semester is over, so I won’t be there twice a week, so I’ve been thinking about other solutions for drilling all the holes.

I could buy a Dremel Drill Press for $35 and have our friends at Amazon deliver it in two days, but there’s a few issues with that, the first of which is, my Dremel tool is old, like really old, like 25 years old maybe? Perhaps more? It belonged to my dad, and maybe even his dad. It’s old, but it works great, and I’m not planning to replace it… and sadly, I don’t think it fits the modern Dremel Drill Press, at least not without modifications.

I’ve also heard from my pals over at Evil Mad Scientist Laboratories that the Dremel Drill Press lacks precision for some jobs. They like the Vanda-Lay Industries Drill Press Plus, which looks pretty solid. It’s not cheap though. There’s also the DIY press Bryan Cera made. I could certainly go the DIY route, and there’s a few other options on Thingiverse to choose from.

Right now though, I probably shouldn’t be spending time trying to DIY up my own solution to a miniature drill press since I can head over to Milwaukee Makerspace and use what we have there. I know we’ve got a “ProtoDrill” thing that drills out boards. It drills from the bottom, and has a foot switch to control it. It didn’t work amazing last year when I tried it, but I’m guessing there’s a few tips to using it I wasn’t aware of. There’s also a bunch of newer Dremel tools and a mini press at the space. The fine folks at Dremel were kind enough to donate some nice tools to us after Maker Faire Milwaukee in 2014.

For my immediate needs, I can drill holes at a variety of makery places around Milwaukee, so I’m not too concerned about a solution for my home shop. I have seen a few generic “rotary tool” drill press stands, which might be easily adaptable to work with my old Dremel tool. If I don’t go the DIY route, I may just grab one of those.

Update: I built my own.

This is just one post in a series, check out the other posts as well: